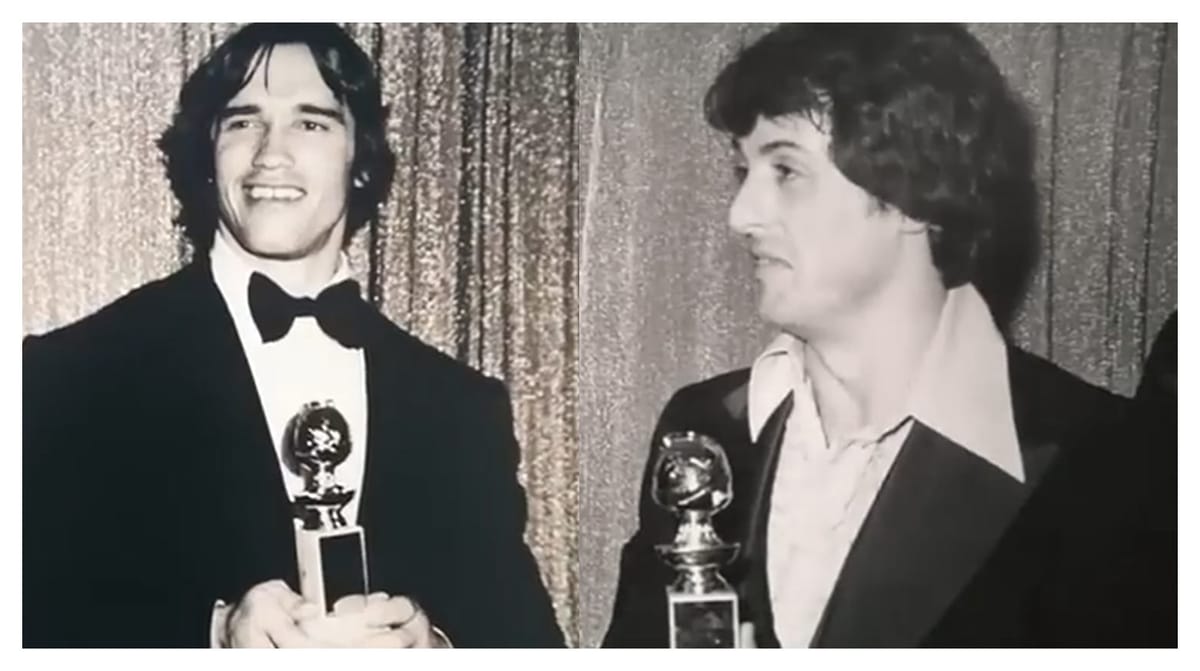

Beef: Schwarzenegger v Stallone: Chapter I

After scaling the heights of the Rocky steps, it seemed like there was no further up for Sylvester Stallone to go. By 1984, Hollywood’s biggest movie star was running on empty. On 22 June that year, his latest movie Rhinestone hit US theatres and was instantly laughed out of town. It was all the more humiliating as this time Stallone had stepped out of his comfort zone: playing loudmouth New York cabbie Nick Martinelli, he is whipped into shape as a country’n’western singer by nightclub veteran Jake Farris (Dolly Parton). Not only did Stallone have to pass muster as a good ol’ boy, donning a fringed jumpsuit that was more upholstery than garment, he had to go toe-to-toe with the queen of Nashville; an effervescent, highly sensitive tuning fork for screen comedy.

The critics made no special allowances. “Embarrassing,” Roger Ebert concluded in the Chicago Sun-Times.[1] “When Mr. Stallone hams it up, [Parton] moves a little to one side and laughs,” observed the New York Times’ Vincent Canby.[2] “Watching it makes a good case for him being shot,” sneered the Daily Texan. With the film raking in just $21 million back of a budget that had ballooned to $28 million thanks to yet another tortuous Stallone shoot, audiences were apparently simpatico. “I guess the public didn’t want to see Sylvester Stallone do comedy – or see me do Sylvester Stallone,” Parton later commiserated in her autobiography.

Stallone was struggling to stake out new territory into which to expand his stardom. Rhinestone was the latest in a series of bombs and second-string offerings he’d trotted out when not making sequels to his generational lightning strike, Rocky. There had been 1978’s Paradise Alley, in which the star tried in vain to drum up repeat Balboa business, only with 1940s wrestlers. In 1981, the urban neo-noir Nighthawks and wartime soccer pic Escape to Victory – featuring the Italian-American as the world’s unlikeliest goalkeeper in the company of the likes of Pelé and Bobby Moore – made a little money.

The actor’s first outing as John Rambo, the beaten-dog, back-to-the-wall Vietnam vet trying to evade government pursuit in 1982’s First Blood gave him some breathing room. It had been a troubled project that Stallone only reluctantly accepted after many big-hitters, like Clint Eastwood, Robert de Niro and Nick Nolte, had passed on it. His monosyllabic focus and thousand-yard-stare sold the material, which still lingered in the gritty badlands of 70s cinema. Grossing $47 million in the US, it reassured Stallone there could be life after Rocky and launched its producers Carolco, the company that was to fuel the 80s action-movie arms race, as a going concern. But it seemed that punters would only accept the actor when he was on their side, in his down-at-heel, proletarian champ mode.

In real life, Stallone was still beset with his more than his fair share of humdrum troubles – ironically for a man who had just sold a mansion with a revolving driveway. The strain of dealing with his son Seargeoh’s autism, diagnosed in 1982, finally shattered his first marriage; his wife Sasha filed definitively for divorce in November 1984. In a classic case of that malady of the 1%, stardom hadn’t eased the self-doubt. With his oscillating box-office fortunes, he tortured himself in the wake of Escape to Victory with the idea that the end was nigh: “I felt that it was over. I was finished. This film would probably be my last. The fame game had gotten to me. I had lost. I had hit basically emotional rock-bottom.”[3] He was still the kid from Hell’s Kitchen once ribbed for his facial paralysis and whom his own father informed: “You weren’t born with much of a brain, so you’d better develop your body.” (A line repeated almost verbatim in Rocky.) The fans who now lionised him for his brand of hard-scrape heroism, constructed from the rubble of his humble upbringing, ironically left him uncertain about his true place in life. “It’s funny, but now there’s this great herd of people who are coming forth and saying, ‘I like you!’ It happened to Rocky too. I feel like saying to them: ‘Where were you when I was living in Hotel Barf, eating hot and cold running disease?’”[4]

He overcompensated in the self-indulgent Hollywood manner. By the early 1980s, he had a reputation as a prima donna, who directed his own movies attired in fur coats, and relentlessly meddled on other people’s sets. Rhinestone was the latest example of his control freakery: the original director Don Zimmerman lasted just three weeks before bitter arguments over aesthetic choices with its star did for him, and he was replaced by Porky’s helmer Bob Clark.

Rocky had proved that Stallone was an able writer with a populist touch. But, once established at Hollywood’s pinnacle, he routinely took advantage to dictate the material. On Rhinestone, Stallone redid the script to place himself at centre-stage and pile it high with crass wisecracks. “I really do have this big organ,” he tells Parton, before taking her to his father’s funeral parlour. The screenwriter whose script he’d trampled, Phil Alden Robinson, took the unusual step of airing his grievances – as much aimed at studio 20th Century Fox as at the star – in public: “If you take a non-housebroken puppy and put him in a nice house and he makes a mess on the floor, you don’t blame puppy – he’s only doing what comes naturally. You blame the person who put him in the house in the first place.”[5]

One straight-talker saw through this chest-puffing and territorial pissings. “Sly is the perfect balance of total ego and total insecurity,” his co-star Parton, with whom he got on well, later remembered. “I always told him he was spectacular, but he had a blind spot where compassion and spirituality ought to be.”[6] Flipping between ego and insecurity was souring Stallone’s reputation; torn between his underdog reliables Rocky and Rambo and the need to break new ground, his indecisiveness risked tarnishing his hard-won stardom too. He had turned down the year’s biggest hit, Beverly Hills Cop, and another top 10 contender Romancing the Stone, to do Rhinestone.

Instead he found himself in another bomb, reeling off a parodic country ditty called Drinkenstein – “Budweiser, you created a monster … ” – while wearing a Technicolor ensemble topped with a coonskin-tasselled fedora. He could’ve been forgiven for thinking: what is it I have turned into here?

A physique upgrade.

On 26 October 1984, the next generation of cinematic monster arrived on the grounds of Los Angeles’s Griffith’s Observatory, wreathed in lightning. Audiences for The Terminator were left gawping as Cyberdyne Systems Model 101 materialised, Arnold Schwarzenegger’s widescreen pectoral configuration – which seemed more designed than gym-built – an upgrade on the sweaty Stallone iteration.

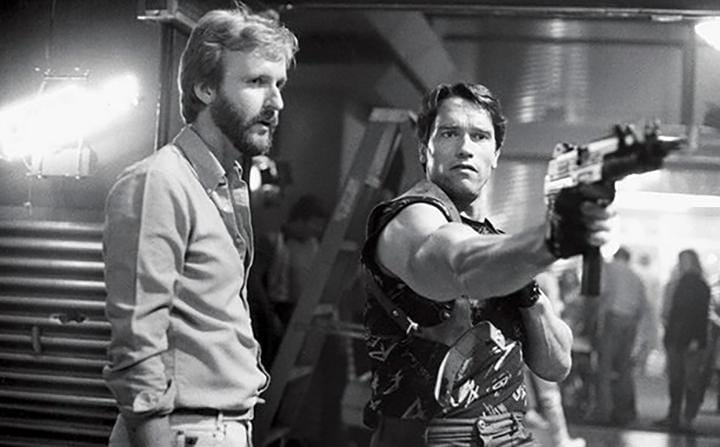

This low-budget B-movie, directed by a jobbing Canadian wannabe called James Cameron, held viewers transfixed with laser-cut precision. Schwarzenegger’s killer robot moved with lethal economy and – uttering just 58 words throughout – spoke that way too. In the script on paper, no one batted an eyelid at “I’ll be back”. But delivered with supreme Teutonic sangfroid it would serve both as a laconic quip and a campaign promise for Schwarzenegger’s assault on megastardom over the decade to come.

The future was here. But the incisiveness of Schwarzenegger’s entry into the big league belied over a decade of planning and toil to get there: not just the victorious 1970s bodybuilding career that made his name in the US, but the struggles of his early acting career to carve himself a niche. With Rocky, Stallone had arguably opened the door for screen heroes rooted in ripped physiques (their mutual inspiration Steve Reeves, who played Hercules in the 1950s, operated at a lower level of fame). But at first muscles only lifted Schwarzenegger part of the way. He lumbered through 1970’s Hercules in New York, took a small part as a dim-bulb cowboy in 1979’s The Villain, then raised his profile with two outings as the Hyborian warrior Conan in the 1980s. But he was struggling to make the studios envisage his usefulness beyond the priapic physique. Only Bob Rafelson’s Stay Hungry in 1976 thought outside of the box and gave his character an interior life that required equal heavy lifting. Though he was a bodybuilder, the enigmatic Joe Santo was the movie’s moral centre (and, weirdly, also a mean hoedown fiddler).

But in all other ways, the Austrian was where he felt he should be. Schwarzenegger had become a naturalised US citizen in September 1983, along with 2,000 others at Hollywood Shrine Auditorium. America had embraced him: he was already a real-estate millionaire and since 1977 in a long-term relationship with Maria Shriver, the niece of John F Kennedy. He had also pledged fealty to the flag of Italian producer Dino de Laurentiis, with Conan the Barbarian the first in a five-picture deal. This was despite irking the maestro at their first meeting by asking: “Why does a little guy like you need such a big desk?”

With a sequel, Conan the Destroyer, quickly rushed into production, Schwarzenegger was already chafing at being “owned” by De Laurentiis. At the end of 1983, another career-boosting disruptor – though very different to Stay Hungry – came along. After Conan, the pedigree of the projects he was offered was on the up. He was weighing up a film about Paul Bunyan, the mythical lumberjack, when Orion Pictures knocked on his door with a sci-fi script called The Terminator. Executive Mike Medavoy suggested the Austrian for the role of Kyle Reese, the soldier sent back in time to protect Sarah Connor, the mother of a future resistance leader in the war against the machines. James Cameron was not enthusiastic about the prospect of having his lines put through the mittel-European mangler, but agreed to meet the actor.

The pair sat down at Schatzi’s, the home-from-home Austrian beerhaus in Santa Monica favoured by Schwarzenegger, and were soon digging into the nuances of Cameron’s “strange” story. Rather than the hyper-earnest Reese, the actor was obsessed with the deadpan killer robot: “One thing that concerns me is that whoever is playing the Terminator, it’s very important he gets trained in the right way. If this guy is really a machine, he won’t blink when he shoots. When he loads a new magazine into his gun. He won’t have to look because a machine will be doing it, a computer. When he kills, there will be absolutely no expression on the face, not joy, not victory, not anything.”[7]

The actor was so fastidious, Cameron pointed out the obvious: “Why don’t you play the Terminator?” But Schwarzenegger, wary of the career-narrowing implications of playing a villain, needed cajoling. From a standpoint of raising his profile, the director pointed out it was the title character he would be playing. Portraying an emotional-less android would also be a true acting challenge, Cameron said, citing Yul Brynner in 1973’s Westworld as a rare success in the field. And it would be a departure for the bodybuilder; this time he would the onus would be on “the face”, not the body. Schwarzenegger, with that jutting Cro-Magnon chin and high-buttressed cheekbones, undeniably had a face.

After settling the bill, Schwarzenegger mused on it and signed on after a day. Describing it to one journalist as “some shit movie I’m doing, take a couple of weeks”,[8] he kept his expectations low – almost purposefully. If The Terminator tanked, it wasn’t so high-profile it would capsize his career. But a few days on Cameron’s shoot, which took place for six weeks in February and March 1984, made him realise this wasn’t B-movie amateur hour; it was total mobilisation.

The director oversaw his cast with pitiless focus, treating them like automatons at the service of his vision. “It was not what I’d call a happy set,” Schwarzenegger later recalled.[9] Cameron would explode if there were any deviations and wasn’t exactly gushing with praise: “If you do something right, he’ll say it was disastrous but probably a human being could do no better. So you walk away going, ‘I guess he likes it.’”[10] One day the lead actor decided The Terminator could up the laugh quotient by having the robot assassin find a beer in someone’s fridge, take a sip and “act silly for a second”. The director – in a tirade that echoed Kyle Reese’s “It doesn’t feel pity” speech – cut him off dead: “It’s a machine, Arnold. It’s not a human being. It’s not ET. It can’t get drunk.”[11]

But seeing the dailies left Schwarzenegger “in awe” of Cameron’s dynamism and attention to detail. He played his part by making good on his interview promise and calibrating the Terminator’s minimalist body language and sepulchral vocal tone. He trained for three months with an arsenal of weaponry – handguns, machine guns, rifles – so he could lock and load as if to the mayhem born. “The thing I learned from my acting teacher was not to act, but to be. So I had to work hard over a period of months learning to be a machine,” he said.[12]

Be, not act, was pragmatic advice given Schwarzenegger’s thespian limitations at the time; Rafelson, for example, opted to shoot him often from the side or back in Stay Hungry, limiting his exposure. But even so, the actor was instinctively synced to how to play the Terminator. It meant embodying him. No blinking, head canted forward on the target, moving through space with loping intent. It wasn’t simply that his bodybuilding career, cycling through millions of reps to perfect his physique and then displaying it to optimal effect on stage, had given him a consciousness of his own frame. The lack of reflection or internalisation, in favour of a ruthless economy of action, was something ingrained in Schwarzenegger; the West Coast Dasein he had adopted in order to leave his Austrian life behind and focus everything as a means to the end of personal success. He claimed to have felt nothing when his brother Meinhard died in a car accident in 1971; when his father Gustav died of a stroke months later, he did not return for his funeral. Self-interrogation didn’t seem to be in his programming. He later wrote: “Why I understood the Terminator is a mystery to me.”[13]

But what you might call a certain callousness translated into a crucial part of his screen persona, where it often appeared with a flippant twist. In the first screenings, audiences cheered the Terminator on, revelling in his shit-talking unilateralism. “You can’t do that,” says a gun vendor, as the robot begins loading a rifle in his shop. Cue the smoking barrels: “Wrong!” In rewiring the villain as cool, rather than weird or sinister, Schwarzenegger allowed the audience to vicariously let their id run riot. “They like to be able to disconnect emotions and go after what they want to go after, destroy what they want to destroy,” he later said.[14] This badass attitude – distilled to sulphuric concentration here from the likes of Dirty Harry and Death Wish in the previous decade – became a crucial ingredient of the 80s action hero.

The id run riot.

Over Schwarzenegger’s initial misgivings, The Terminator was his star-making performance. He carried himself accordingly on set, according to Brian Thompson, the actor who played the hoodlum disembowelled by a nude Terminator at the beginning. “People would ask him if he wanted a bathrobe between shots. He would stand there smoking a cigar, saying: ‘No, I’m fine.’ On the sidewalk of the Griffith Observatory completely butt-naked. His drug of choice is attention. He loves people looking at him.”[15] Schwarzenegger inhaled all of the oxygen out of the room for the ensuing publicity campaign, never acknowledging co-star Linda Hamilton in his interviews. Despite losing airtime to Amadeus, Orion’s awards contender, and dumped into an October release slot, it still made nearly $40m – many times its $6.5m budget and trouncing David Lynch’s Dune and 2010, two notable sci-fi competitors.

Some critics took the obligatory cheap shots at Schwarzenegger, but others recognised a quantum leap for action cinema. “In shades, Arnie is Clint Eastwood on steroids,” wrote the Corvallis Gazette-Times’s Heather McClenaghan. Sid Smith, in the Chicago Tribune, acknowledged the new cyborg hybrid of violence and humour: “An often deadly combination, here the schizoid style helps, providing a little humor just when the sci-fi plot turns too sluggish or the dialogue too hokey.” Much of the critical corps was left in a singed heap. “The road of excess may not lead to the palace of wisdom, but it sure is fun,” wrote the Washington Post’s Paul Attanasio.

The bulldozing Schwarzenegger, not the lithe Michael Biehn – who played Kyle Reese – was the breakout of The Terminator. But the paradox was that this monolithic meathead fundamentally thrived on competition. He had competed for his parents’ affections with his supposedly smarter, better-looking brother Meinhard. His bodybuilding career was an annals of mind games and psyche-outs, notably towards Sergio Oliva and Lou Ferrigno, the latter of whom he hazes mercilessly in the documentary Pumping Iron.

And now in cinema, he had Sylvester Stallone in his sights. Ever-pragmatic, the first metric to figure in the up-and-comer’s robo-vision for measuring their respective stardom was money: his $750,000 salary for The Terminator was a long way off Stallone’s $3.5 million for First Blood or $4m for Rhinestone. “I said to myself: hey, this is the guy that I have to pass if I want to be the top-paying action star,” he later remembered. “Because he was the action guy when I came onto the scene, I always had Sly in front of me. I was chasing him.”[16]

[1] https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/rhinestone-1984

[2] https://www.nytimes.com/1984/07/29/arts/film-view-post-mortem-on-a-couple-of-flops.html

[3] ‘The Trouble with Sylvester Stallone’, Rolling Stone, Lewis Grossberger

[4] Stallone: A Rocky Life, Frank Sanello, p79.

[5] ‘The Rocky Road to a Hollywood Flop’, Michael London, Los Angeles Times, 20 July 1984

[6] ‘How I Came Close to Suicide’, Cliff Jahr, Ladies Home Journal, June 1896

[7] Total Recall, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Chapter 16

[8] Rick Wayne, quoted in True Myths, Nigel Andrews, p104

[9] Total Recall, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Chapter 16

[10] Premiere magazine, August 1994, J Richardson

[11] Total Recall, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Chapter 16

[12] Fantastic: The Life of Arnold Schwarzenegger, Laurence Leamer, p197

[13] Total Recall, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Chapter 16

[14] Playboy interview, Jane Goodman, January 1988.

[15] Author interview

[16] Fantastic: The Life of Arnold Schwarzenegger, Laurence Leamer, p204

Member discussion